Kythera… my island home

Santorini, Mykonos, Crete, Paros.

Bet you’ve been there, strolled past the white-washed houses, tasted the moussaka and drunk the ouzo.

Yamas!

These are all gorgeous, albeit very-touristy islands. And rightly so. They ooze the essence of Greek island life with their bougainvillea-lined cobblestone laneways and evocative taverna lifestyle. Who doesn’t dream of living a Greek island lifestyle?

Except that the Greek island lifestyle wasn’t always so picturesque.

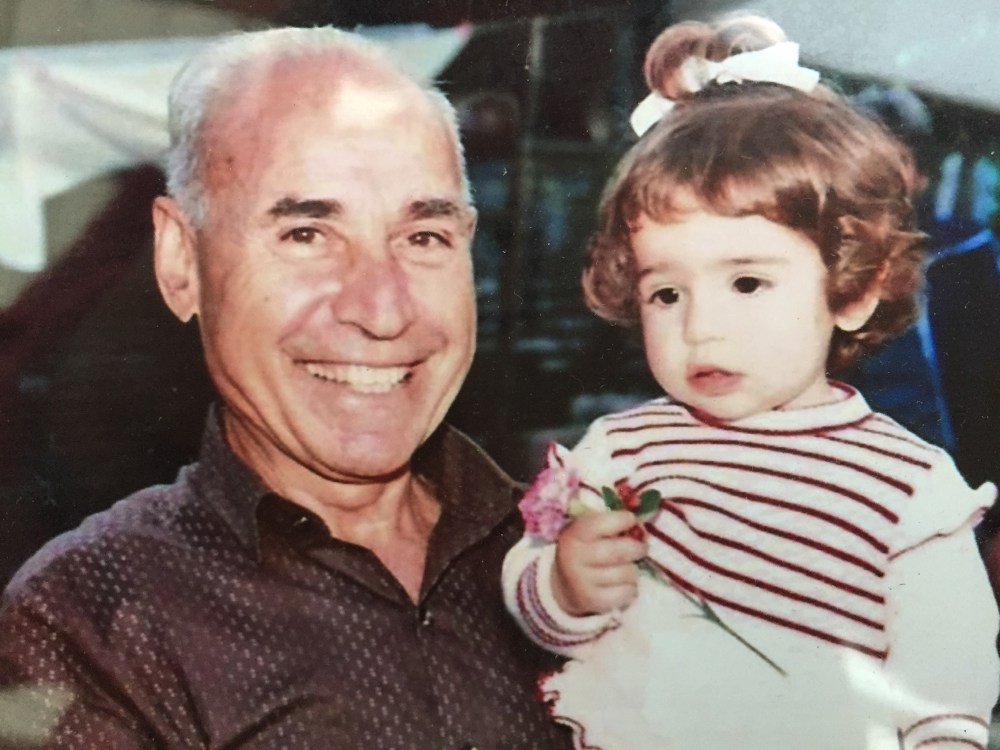

If it was, my papouthes and yiayathes would not have fled in the 1930s and 1940s respectively to start new lives in Australia.

Their Greek island was especially exposed. Its strategic location in the Ionian Sea had made it a red hot target through history and any conqueror worth their sea salt made their way there; Venetians, Turks, French, English, Nazis…… when my Thea Marika once pointed to the second-story of the family home dating to the 1500s and told me they used to hurl hot oil through the window to scare the pirates below – she wasn’t kidding.

That island is Kythera.

Where you ask?

Exactly.

With the pirates now less of an issue, Kythera is the under-the-radar Greek island that you’ve never heard about and with any luck it will stay that way. Its strategic location, marooned between the Peloponnese and Crete, was a drawcard for those pirates but doesn’t suit modern-day travellers. You can’t ferry hop easily the way you can between the Cycladic islands. There’s only one flight a day in summer in a plane that fits 20 people. Traverse the island’s perilous roads in a bus at your peril. Mass tourism is literally not possible.

Which means that the only non-locals you encounter when you visit are the other Kytherian-Aussies who visit in droves in the summer months. Locating my extended family is as easy as strolling along Kapsali beach on my way to have a frappe.

It feels indulgent to have 100% lineage from one single island. To have visited the houses where my grandparents grew up and walked through villages bearing their name, e.g. Kastrissianika which is named after my Papou Con’s family. (Side note: where is the village of Megaloconomosanika?).

Being in Kythera reawakens part of my culinary soul. Of course I was eating the delicious food that originated from Kythera from the moment I started on solids. And many traditions followed my family across the sea to their new homes in Australia. But being in my homeland connects me to those traditions like configuring pieces of a puzzle.

Olives – the bedrock of Greek culture – are a good place to start. The foliage makes up crowns, the fruit is delicious to eat and the oil is essential in rituals (and deters those pesky pirates). I’ve always maintained that the secret to Greek cooking is 50% love and 50% olive oil. But that never feels as prescient as it does when I am standing in the olive groves that have been part of my family’s subsistence for over 100 years. While one olive tree looks the same as the next (at least to me), what sets this grove apart is the hut at the back that my Papou Peter built when he was a teenager so he would have somewhere to sleep when spending long days tending to the trees.

The other main source of subsistence was horta, or wild greens, which I have written about before in an effort to explain why Greeks love weeds. Not a single meal on my recent trip passed without a bowl of vlita on the table with lemon and olive oil.

“Give me horta and horiatiki (Greek salad) and I’m happy” declared mum.

It’s hard to find the exact same greens in Australia. There were murmurs of smuggling in seeds from Kythera so we could recreate the exact breeds here. I’m fairly sure the older generations did exactly that.

While vlita is in season during summer it switches to rathikia a few months later. Eating in season is the only way Greeks eat and it’s a revelation. You want figs in July? Go home and come back in August because that’s when they’re in season and that’s when you’ll get them. Not a moment before or after.

That’s the reason why kolokythi, zucchini, was in every second dish while we were in Kythera. It was in season, it tasted great, so the entire island got involved. The idea of bringing in produce from elsewhere so it’s always available is never a consideration. We ended one meal with fresh karpouzi or watermelon. Our host noted that watermelon wasn’t grown on the island and it had come from the Peloponnese, in a tone of regret that implied the Peloponnese was a far-flung foreign country versus being the Greek mainland.

That was a particularly memorable lunch. It started at 3.30pm, which seems ridiculous until you consider that dinner is usually eaten around 10pm. Once you acclimatise to Greek time you never look back.

The cocky foodie in me thought I had Greek sweets down pat. I’ve been known to eat galaktoboureko for breakfast and will move heaven and earth to track down the best bougatsa in town. I didn’t expect to unearth a new (for me) sweet and was delighted when I did. It was mum who put portokalopita on my radar and we ate our way through copious amounts while on the island. It’s made from phyllo drenched in orange syrup and I am now officially obsessed. No Greek cake shop in Sydney seems to make it (why, why?!!) so I will have to turn my hand to it instead.

It would be remiss of me to talk about Kythera without talking about the sea. The waters around the island are special, but don’t take my word for it. The ancient poet Hesiod recounts in his epic Theogony that Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, was born in the foam of the sea of Kythera. As far as I’m concerned we’re distant cousins and I’ve forgiven her for defecting to Cyprus.

The influence of the sea is strong in my family. Both of my papous were in the Greek navy. By the time they came to Australia their maritime roots ran deep and profoundly influenced their lives. My Papou Peter was a deep-sea fisherman and also the seafood chef at the Royal Automobile Club. My dad was the lucky kid at school with lobster sandwiches in his lunchbox.

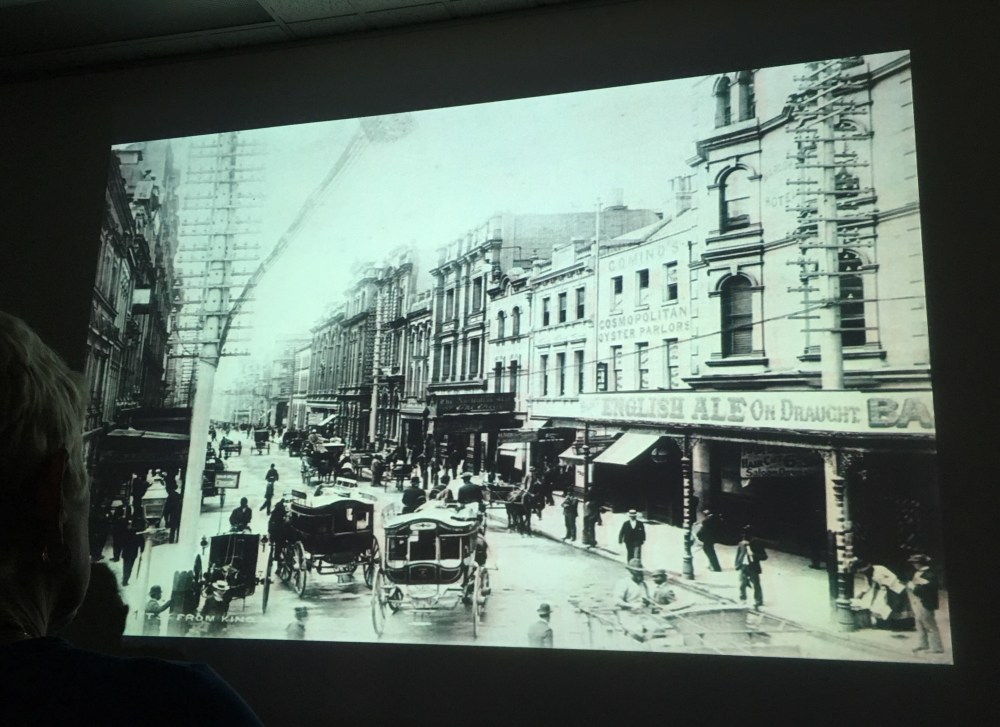

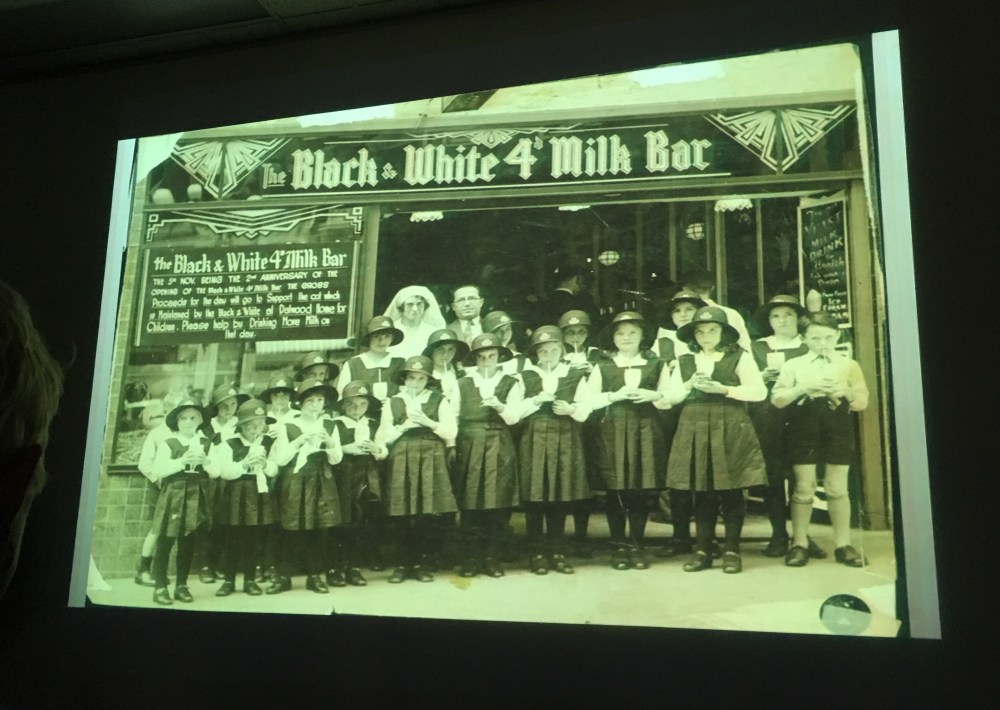

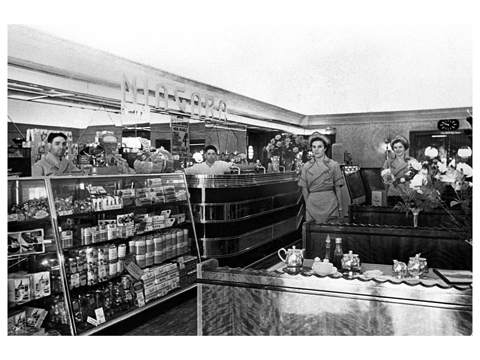

My Papou Con ran the most buzzing fish shop in Sydney in the 1950s and 1960s – Wynyard Fish Supplies – with his brothers. It was the go-to place for city workers to pick up their seafood essentials, especially on a Friday.

Greek food is never just about the food. It’s the vessel that brings loved ones together to share, laugh and live life. Holidays in Kythera revolve around your morning frappe, which taverna to meet at for lunch (Pierros in Livadi or Lemonokipos in Karavas?), and where to reconvene in the evening. On Sundays, the bulk of the 4,000 strong island gravitates to Potamos for the Sunday market and the chance to reunite with friends, complain over coffee and peruse the local gliko (spoon sweets) or ladi (oil). If the entire island didn’t already know you were in Kythera, they do now.

The beauty of Kythera is not just Aphrodite’s legacy. It’s not only the sand, sea and sweet smell of golden grass and olive wood (so intoxicating that French luxury brand Hermès has bottled it into a fragrance – Un Jardin a Cythere). Kythera is the origin story for this fidgety foodie and a place that will always feel like home.